About Acromegaly

What is Acromegaly?

Acromegaly is a hormonal disorder that results from too much growth hormone (GH) in the body. The pituitary, a small gland in the brain, makes GH. In acromegaly, the pituitary produces excessive amounts of GH. Usually the excess GH comes from benign, or noncancerous, tumors on the pituitary. These benign tumors are called adenomas.

Acromegaly is most often diagnosed in middle-aged adults, although symptoms can appear at any age. If not treated, acromegaly can result in serious illness and premature death. Acromegaly is treatable in most patients, but because of its slow and often “sneaky” onset, it often is not diagnosed early or correctly. The most serious health consequences of acromegaly are type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, increased risk of cardiovascular disease, and arthritis. Patients with acromegaly are also at increased risk for colon polyps, which may develop into colon cancer if not removed.

When GH-producing tumors occur in childhood, the disease that results is called gigantism rather than acromegaly. A child’s height is determined by the length of the so-called long bones in the legs. In response to GH, these bones grow in length at the growth plates—areas near either end of the bone. Growth plates fuse after puberty, so the excessive GH production in adults does not result in increased height. However, prolonged exposure to excess GH before the growth plates fuse causes increased growth of the long bones and thus increased height. Pediatricians may become concerned about this possibility if a child’s growth rate suddenly and markedly increases beyond what would be predicted by previous growth and how tall the child’s parents are.

Video: What is Acromegaly? (View all chapters of this series on our Resources page)

What causes acromegaly?

Acromegaly is caused by prolonged overproduction of GH by the pituitary gland. The pituitary produces several important hormones that control body functions such as growth and development, reproduction, and metabolism. But hormones never seem to act simply and directly. They usually “cascade” or flow in a series, affecting each other’s production or release into the bloodstream.

GH is part of a cascade of hormones that, as the name implies, regulates the physical growth of the body. This cascade begins in a part of the brain called the hypothalamus. The hypothalamus makes hormones that regulate the pituitary. One of the hormones in the GH series, or “axis,” is growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH), which stimulates the pituitary gland to produce GH.

Secretion of GH by the pituitary into the bloodstream stimulates the liver to produce another hormone called insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I). IGF-I is what actually causes tissue growth in the body. High levels of IGF-I, in turn, signal the pituitary to reduce GH production.

The hypothalamus makes another hormone called somatostatin, which inhibits GH production and release. Normally, GHRH, somatostatin, GH, and IGF-I levels in the body are tightly regulated by each other and by sleep, exercise, stress, food intake, and blood sugar levels. If the pituitary continues to make GH independent of the normal regulatory mechanisms, the level of IGF-I continues to rise, leading to bone overgrowth and organ enlargement. High levels of IGF-I also cause changes in glucose (sugar) and lipid (fat) metabolism and can lead to diabetes, high blood pressure, and heart disease.

Pituitary Tumors

In more than 95 percent of people with acromegaly, a benign tumor of the pituitary gland, called an adenoma, produces excess GH. Pituitary tumors are labeled either micro- or macro-adenomas, depending on their size. Most GH-secreting tumors are macro-adenomas, meaning they are larger than 1 centimeter. Depending on their location, these larger tumors may compress surrounding brain structures. For example, a tumor growing upward may affect the optic chiasm—where the optic nerves cross—leading to visual problems and vision loss. If the tumor grows to the side, it may enter an area of the brain called the cavernous sinus where there are many nerves, potentially damaging them.

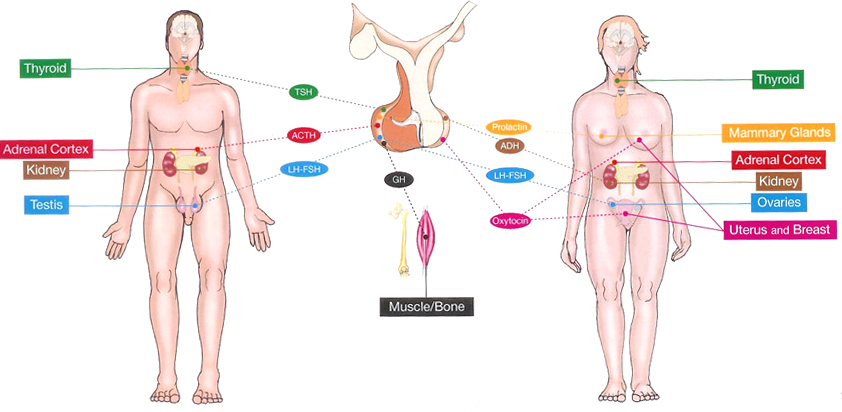

Compression of the surrounding normal pituitary tissue can alter production of other hormones. These hormonal shifts can lead to changes in menstruation and breast discharge in women and erectile dysfunction in men. If the tumor affects the part of the pituitary that controls the thyroid—another hormone-producing gland—then thyroid hormones may decrease. Too little thyroid hormone can cause weight gain, fatigue, and hair and skin changes. If the tumor affects the part of the pituitary that controls the adrenal gland, the hormone cortisol may decrease. Too little cortisol can cause weight loss, dizziness, fatigue, low blood pressure, and nausea.

Some GH-secreting tumors may also secrete too much of other pituitary hormones. For example, they may produce prolactin, the hormone that stimulates the mammary glands to produce milk. Rarely, adenomas may produce thyroid-stimulating hormone. Doctors should assess all pituitary hormones in people with acromegaly.

Rates of GH production and the aggressiveness of the tumor vary greatly among people with adenomas. Some adenomas grow slowly and symptoms of GH excess are often not noticed for many years. Other adenomas grow more rapidly and invade surrounding brain areas or the venous sinuses, which are located near the pituitary gland. Younger patients tend to have more aggressive tumors. Regardless of size, these tumors are always benign.

Most pituitary tumors develop spontaneously and are not genetically inherited. They are the result of a genetic alteration in a single pituitary cell, which leads to increased cell division and tumor formation. This genetic change, or mutation, is not present at birth, but happens later in life. The mutation occurs in a gene that regulates the transmission of chemical signals within pituitary cells. It permanently switches on the signal that tells the cell to divide and secrete GH. The events within the cell that cause disordered pituitary cell growth and GH oversecretion currently are the subject of intensive research.

Nonpituitary Tumors

Rarely, acromegaly is caused not by pituitary tumors but by tumors of the pancreas, lungs, and other parts of the brain. These tumors also lead to excess GH, either because they produce GH themselves or, more frequently, because they produce GHRH, the hormone that stimulates the pituitary to make GH. When these non-pituitary tumors are surgically removed, GH levels fall and the symptoms of acromegaly improve.

In patients with GHRH-producing, non-pituitary tumors, the pituitary still may be enlarged and may be mistaken for a tumor. Physicians should carefully analyze all “pituitary tumors” removed from patients with acromegaly so they do not overlook the rare possibility that a tumor elsewhere in the body is causing the disorder.

How common is acromegaly?

Small pituitary adenomas are common, affecting about 17 percent of the population. However, research suggests most of these tumors do not cause symptoms and rarely produce excess GH. Scientists estimate that three to four out of every million people develop acromegaly each year and about 60 out of every million people suffer from the disease at any time. Because the clinical diagnosis of acromegaly is often missed, these numbers probably underestimate the frequency of the disease.

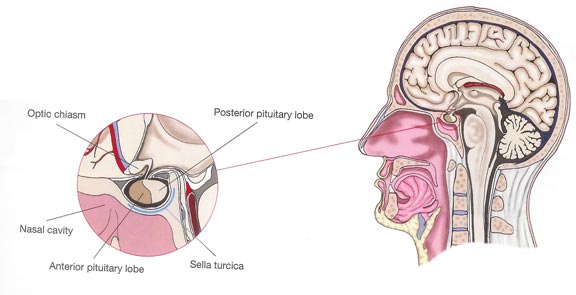

What is the pituitary gland and where is it located?

The pituitary is a small gland (no larger than a pea) located at the base of the brain near the optic nerves. It rests in a saddle-like compartment in the skull called the “sella turcica”. The pituitary gland plays a key role as the master gland of the endocrine system. It receives information from the brain via the hypothalamus and produces hormones that are important to the Functioning of other organs. These hormones are released in the blood circulation in order to reach their target organs.

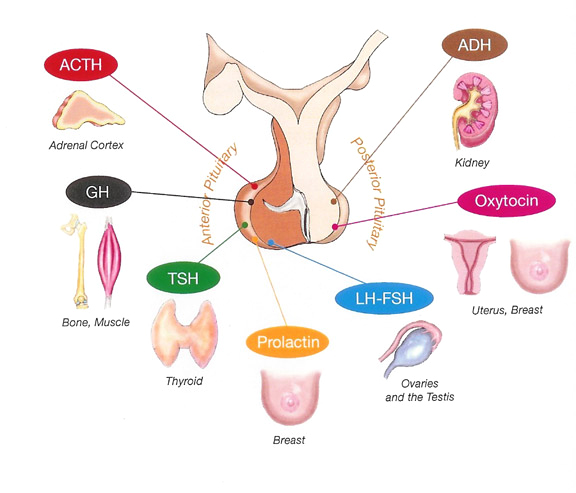

The pituitary is composed of two lobes: the posterior lobe and the anterior lobe (called adenohypophysis) containing the five hormone-secreting cell types. The pituitary posterior lobe stores two hormones produced by the hypothalamus: antidiuretic hormone (ADH) important for water reabsorption and oxytocin important for uterine contractions. The pituitary anterior lobe is comprised of live different cells, each producing a corresponding hormone.

- One cell type (corticotrophs) produces adrenocorticotropin (ACTH) that stimulates the release of glucocorticoid by adrenals, contributing to normal blood pressure and

electrolyte balance. - The second cell type (thyrotrophs) produces thyroid- stimulated hormone (TSH) that stimulates thyroid hormones release by thyroid gland, contributing to metabolism.

- The third type (gonadotrophs) secretes gonadotrophins (LH and FSH) that regulate sexual Function and reproduction.

- The fourth type (lactotrophs) produce prolactin, the hormone ol-lactation.

- Finally, the somatotrophs produce GH that stimulates the production of insulin growth factor 1 (IGP-1) by the liver, regulating the growth.

What is a pituitary adenoma?

Each anterior pituitary cell type may proliferate or multiply leading to a pituitary adenoma. In case of acromegaly, a somatotroph adenoma arises from GH-producing cells and is the source of the excessive release of GH. Pituitary adenomas may also be mixed and co-secrete prolactin and GH. The mechanisms by which normal pituitary cells proliferate are not well known. Some genetic factors have been implicated, but familial acromegaly is very rare.

Pituitary adenomas are either microadenomas (tumors less than l cm) or macroadenomas (greater than l cm). They can be noninvasive (contained within the sella turcica) or invasive (extending beyond the sella).

As the adenoma grows, it may exert pressure on nearby structures within the brain, such as the optic chiasm and the normal pituitary thereby impairing its Function. It may thus cause headaches, visual disturbances and abnormal pituitary function also called hypopituitarism. This is characterized by loss of strength (asthenia), low blood pressure, hypothyroidism, menstrual cycle disturbances in women and erectile dysfunction in men. When hypopituitarism is present, hormonal replacement therapy is needed.

It was certainely amazing to see others with this condition, to hear how they were diagnosed and the effects this condition has had on their physical and family life. We meet again in the fall of 2005 and agreed to meet twice per year, in the spring and fall. We set up a phone tag list for each of us to phone when ever we felt we needed support. On April 20th of 2006 we successfully formed the Atlantic Acromegaly Support Society. We, at this time, still meet twice per year.

Our goal at our meetings is to have a Guest Speaker who will speak about the conditions and treatments available to us in the different fields that we need to be seen for the clinics (e.g. Endocrinology, neurology, radiology etc.). We have had some GREAT presenters so far. We have approximately 50 patients who have been diagnosed with Acromegaly within the Atlantic Provinces and there are approximately 25, who attend our meetings to date.